Musculoskeletal injuries in tennis

- 08/10/2019

In recent decades, tennis, in particular, and racquet sports in general, have experienced a significant increase in fans, remaining in the top ten most practiced sports in our country. Musculoskeletal pathologies associated with tennis are highly varied and, generally, although they can manifest acutely, are usually caused by repetitive microtraumas:

- The upper limb is by far the anatomical area where most injuries are found, and within this group, the shoulder is the joint with the highest incidence of injuries.

- Possibly the second most frequently affected area is the spine. Playing tennis subjects the spine to hyperflexion, hyperextension, and rotation, which often cause various types of injuries.

- Other joints, such as ankles, knees, feet, and hips, are also subjected to overload and therefore experience various injuries.

What are the most common shoulder injuries in tennis?

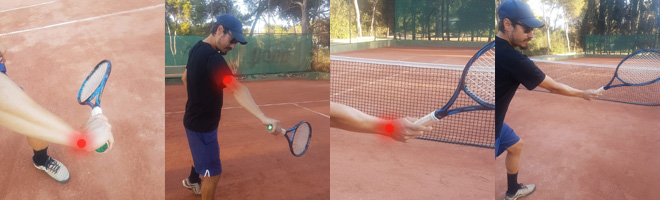

It can be affected by various pathologies, the majority of which are the repetitive microtraumas to which the shoulder joint is subjected, especially due to the demand and importance in the game of one of its fundamental aspects: the serve (Figure 1). Although the most frequent processes are tendonitis and acute inflammatory processes, we describe below four important injury conditions that occur in the practice of both professional and amateur tennis:

Figure 1: Different phases of service

Impingement syndrome or subacromial syndrome:

Perhaps one of the most common, it causes shoulder pain due to a space conflict between its container (acromiocoracoid space) and its contents (rotator cuff and bursa). The clinical diagnosis is pain and functional impairment of varying degrees, supported by tests such as X-rays, ultrasound, or MRIs.

Initial treatment is conservative, with sports rest, anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, and functional rehabilitation, reserving infiltration therapy for those who fail to improve with these initial measures.(See article on ultrasound-guided infiltration of the subacromial bursa).

A high percentage will respond to this initial treatment. In cases of non-improvement, arthroscopic surgery may be indicated.

Acromioclavicular arthropathy:

The acromioclavicular joint will be compromised in high-range movements performed at high speed and repetitively. It almost always affects the dominant shoulder and occurs after the age of 25. There are three movements during tennis practice that can affect this joint. Diagnosis is primarily clinical and supported by radiological X-rays and ultrasound. Treatment is the usual treatment of rest and anti-inflammatory drugs, and in some cases, ultrasound-guided intra-articular corticosteroid injections. Few cases require surgical intervention.

Anterior shoulder subluxation:

Repetitive trauma in the smash or serve causes weakness of the anterior shoulder complex and can lead to injuries to the glenoid labrum or the anteroinferior border of the glenoid. It manifests as severe pain at the end of the stroke with a sensation of loss of strength. Treatment is usually conservative.

Long Thoracic Nerve Neuropathy:

A long nerve originating in the cervical spine and responsible, among other nerves, for innervating the serratus anterior muscle. Again, the smash and the serve are two tennis movements that can cause neuropathies due to repetitive microtrauma. It manifests as pain and functional weakness in the shoulder with a sensation of loss of strength and scapula alata, which appears when the medial border of the scapula lifts off during active raising and lowering of the arm. (Figure 2). Physical therapy will focus on targeted active therapy of the shoulder girdle and the functional recovery of the serratus anterior muscle.

Figure 2: Raising and abrupt lowering of the arm during service and smash

Suprascapular nerve neuropathy:

Responsible for innervation of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, it can be affected by smash and serve shots (again, the most technically and anatomically demanding). Three movements can compromise this nerve:

- Horizontal adduction.

- Horizontal retropulsion of the shoulder plus external rotation.

- Antepulsion plus internal rotation.

The suprascapular nerve passes through two notches (the suprascapular notch, before which it gives its innervating branch to the supraspinatus muscle, and the spinoglenoid notch, after which it gives innervation to the infraspinatus muscle). For this reason, the symptoms of this neuropathy can vary depending on the location of the nerve injury. Sports rest, ultrasound-guided infiltration therapy, and, in cases refractory to conservative treatment, surgical release of the nerve can restore functionality, complementing treatment with active and progressive re-education at the first signs of reinnervation.

The suprascapular nerve passes through two notches (the suprascapular notch, before which it gives off its innervating branch to the supraspinatus muscle, and the spinoglenoid notch, after which it gives off its innervating branch to the infraspinatus muscle). For this reason, the symptoms of this neuropathy can vary depending on the location of the nerve injury. Sports rest, ultrasound-guided infiltration therapy, and, in cases refractory to conservative treatment, surgical nerve release can restore functionality, complementing treatment with active and progressive re-education at the first signs of reinnervation.

What are the most common elbow injuries in tennis?

Few joints have such a direct relationship with sport as this case. The term epicondylitis or tennis elbow refers to epicondylar pain that encompasses a series of pathologies of the anterolateral aspect of the elbow, with the potential to radiate down the forearm. There are several pathologies that cause pain in this area:

- Pathology Insertional. Alterations in the insertion of the forearm extensor muscles into the epicondyle.

- Radiohumeral joint injuries.

- Radial nerve neuropathies.

- Pain radiating from the cervical spine.

- Most of these are due to repetitive movements and repeated microtrauma caused by backhand hitting. Other factors, in this case extrinsic, may include technical or material defects, racquets, string tension, etc.

Figure 3: Phases of the one-handed backhand

In the backhand stroke, we go from an extended elbow and wrist flexion with maximum tension to a position of elbow extension and maximum wrist extension, causing overload of the extensor muscle insertion. (Figure 3)

Treatment will depend on the diagnosis. In cases of insertional pathology, rest, anti-inflammatory treatment, and in some cases ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injections, physical therapy (stretching, eccentric exercises, etc.), followed by re-education and correction of the factors involved (selection of equipment and improvement of the hitting technique) are recommended. In epicondylitis that has lasted more than three months and does not respond to conservative treatment, ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections may be indicated. (See article on epicondylitis and PRP). Mention should be made of cases of epitrochleitis (the same pain as the elbow, but internal), although not typical of this sport, which can occur in tennis players (at the end of the serve and on the forehand). In children ages 9 to 13, keep in mind PANNER disease (osteonecrosis of the humeral condyle).

What are the most common wrist injuries in tennis?

Greater power in the stroke and the topspin forehand (Figure 4) have led to an increase in pathologies in this sport, most of which are mild tendonitis or overload. Furthermore, synovial cysts on the back of the wrist and fractures of the uncinate process of the hamate bone are not uncommon. The latter presents as pain in the ulnar border of the hand and wrist, with prior trauma (a fall with wrist hyperextension) or without prior trauma as a result of repeated microtrauma from driving or smashing. Conservative treatment is once again essential.

Figure 4: Top-spin drive

What are the most common spinal injuries in tennis?

Although all vertebral segments can be affected, the lumbar spine is by far the most affected. The abruptness of rotations, flexions, and extensions of the lumbar segment, combined with factors such as age, lack of training, previous lumbar pathologies (spondylosis, degenerative disc disease, vertebral listhesis), associated with technical defects, and demanding movements such as serving, explain this area's vulnerability and predisposition to injury. (Figure 5)

Figure 5: Anterior flexion, hyperextension and lumbar rotation movements.

What are the most common musculoskeletal injuries in tennis?

Regarding musculotendinous injuries, two deserve special mention due to their specificity to this sport: tennis leg and contralateral rectus abdominis injury (Figure 6).

- Tennis leg: The sudden and forceful start with the knee fully extended and the ankle dorsiflexed causes disinsertion of the medial gastrocnemius. This injury typically affects people over 40 years of age, associated with other factors such as poor prior training, environmental factors, dietary factors, etc. Clinically, it produces a sudden pain (the stone-hit sign), often with an audible click, and severe functional impairment. Radiological tests confirm the diagnosis, primarily ultrasound, which also allows for follow-up and prognosis. Treatment is conservative in the vast majority of cases, with immobilization for 3-4 weeks, followed by physical therapy and subsequent rehabilitation.

- Contralateral rectus abdominis muscle injury: This occurs due to a sudden contraction of the contralateral abdominal muscles during the final phase of exercise. It is sometimes preceded by overexertion, lack of warm-up, etc. The pain presents as a muscle strain or tear in the contralateral lower abdominal region. Ultrasound will assist the clinical diagnosis.

Figure 6: Mechanisms of tennis leg production and rectus abdominis injury.

What are the most common tendon injuries in tennis?

High physical demands, prolonged exertion, and constant changes in rhythm and acceleration make tendon strains and injuries very common in tennis. At the level of the upper extremity, the smash and the serve are the two technical movements that most compromise the supraspinatus tendon and the long head of the biceps brachii. The topspin forehand frequently causes radial styloiditis and tendonitis of the first extensor compartments, and the forehand backhand and volley cause ulnar styloiditis and strain of the ulnar margin of the wrist. Likewise, triceps brachii tendonitis is related to the slice backhand (Figure 7). Disproportions of the upper and lower body associated with a lack of elasticity make adductor tendonitis possible, especially with forced lateral movements (Figure 8). Other common tendon conditions include patellar tendonitis, goose foot tenosynovitis, insertional tendonitis of the peroneal tendons, posterior tibial tendon, and Achilles tendon tendinopathies (partial/complete ruptures of this tendon are not uncommon).

Figure 7: Mechanisms of production of radial styloiditis, tricipital tendonitis and ulnar styloiditis.

What are the most common joint injuries in tennis?

Having already discussed joint pathology in the upper extremity, let's focus on the lower extremity. While the hip joint is more prone to periarticular involvement due to muscular and tendon processes, and the knee is not particularly exposed (meniscal injuries, chondropathies, etc., are evident), the ankle joint is particularly affected in tennis players. External ligament involvement due to forced varus torsades de pointes (Figure 8), osteochondral talar injuries, etc., are common.

Regarding the foot, various conditions occur, all related to overload, structural alterations of the foot, footwear, and playing surfaces, such as plantar fasciitis (see article on plantar fasciitis) and stress fractures (mainly occurring at the level of the 2nd and 3rd metatarsals).

Without a doubt, all of these injuries are preventable by building a baseline physical capacity, avoiding overload (a common source of injury), creating recovery periods between workouts, regulating the intensity, frequency, and duration of workouts, and compensating as much as possible for the asymmetry inherent in tennis through complementary exercises.

Figure 8: Mechanisms of external lateral ankle ligament injuries and adductor injuries.

Book an appointment with Dr. Jordi Jiménez. He will see you at the center of Palma de Mallorca and help you regain your quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank David Alfaro and Rafael Baena, managers and coaches of Club Tenis Delta, for their collaboration and technical and iconographic advice in the production of this publication.

![[VIDEO] Ultrasound-Guided Injection for Trigger Finger](https://drjordijimenez.com/imagen/100/100/Imagenes/infiltracion-ecoguidada-dedo-resorte-drjordijimenez.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Ultrasound-guided infiltration of the lumbar facets](https://drjordijimenez.com/imagen/100/100/imagenes-pagina/sindrome-facetario-lumbar-drjordijimenez (1).jpg)

![[VIDEO] Ultrasound-guided infiltration of the hip joint](https://drjordijimenez.com/imagen/100/100/Imagenes/valgo-dinamico-rodilla-drjordijimenez.jpg)